We’ve Come a Long Way, Fast

How Technology is Shaping the Modern Classroom in Unseen Ways

My first year in education predates the widespread usage of computers in classrooms. Looking back on it now, the largely analog experience is a vestige of a bygone era – one in which terms like BYOD, CBI, and Web3 were not yet popularized or even coined. As a teacher, my day-to-day stress was derived from, and reserved for, the capriciousness of the copy machine, as opposed to the connectivity of my laptop.

I look back on my first year teaching with fondness, but not with any great longing for the days before technology was present in schools. For students and teachers, the presence of technology has been largely beneficial. A decade ago, education was a more siloed and proprietary experience than it is today – there wasn’t, for example, a readily, and in cases freely, accessible online glossary of materials and resources for teachers and students to avail themselves of. In today’s classroom, students and teachers are both well positioned to learn, grow, and thrive in ways that were previously unimaginable in both scope and and equitability.

On balance, technology has enhanced and enriched teaching and learning. Research has found that the deliberate and developmentally-appropriate integration of technology by skilled teachers has been shown to increase collaboration, facilitate peer-to-peer interactions, personalize learning opportunities, spark student imagination, curiosities, and inquisitiveness, and enable a data-informed learning experience for students. However, there are no panaceas in education. The ubiquity and prominence of educational technology is something of a double-edged sword. For all of its myriad benefits, there are an equal number of challenges. These challenges are well documented in the literature, many of which simply cite the fact that there is not enough longitudinal data to make sense of the long-term ramifications of technology on teaching and learning. And this is why I found a recent report from Builtin so astonishing.

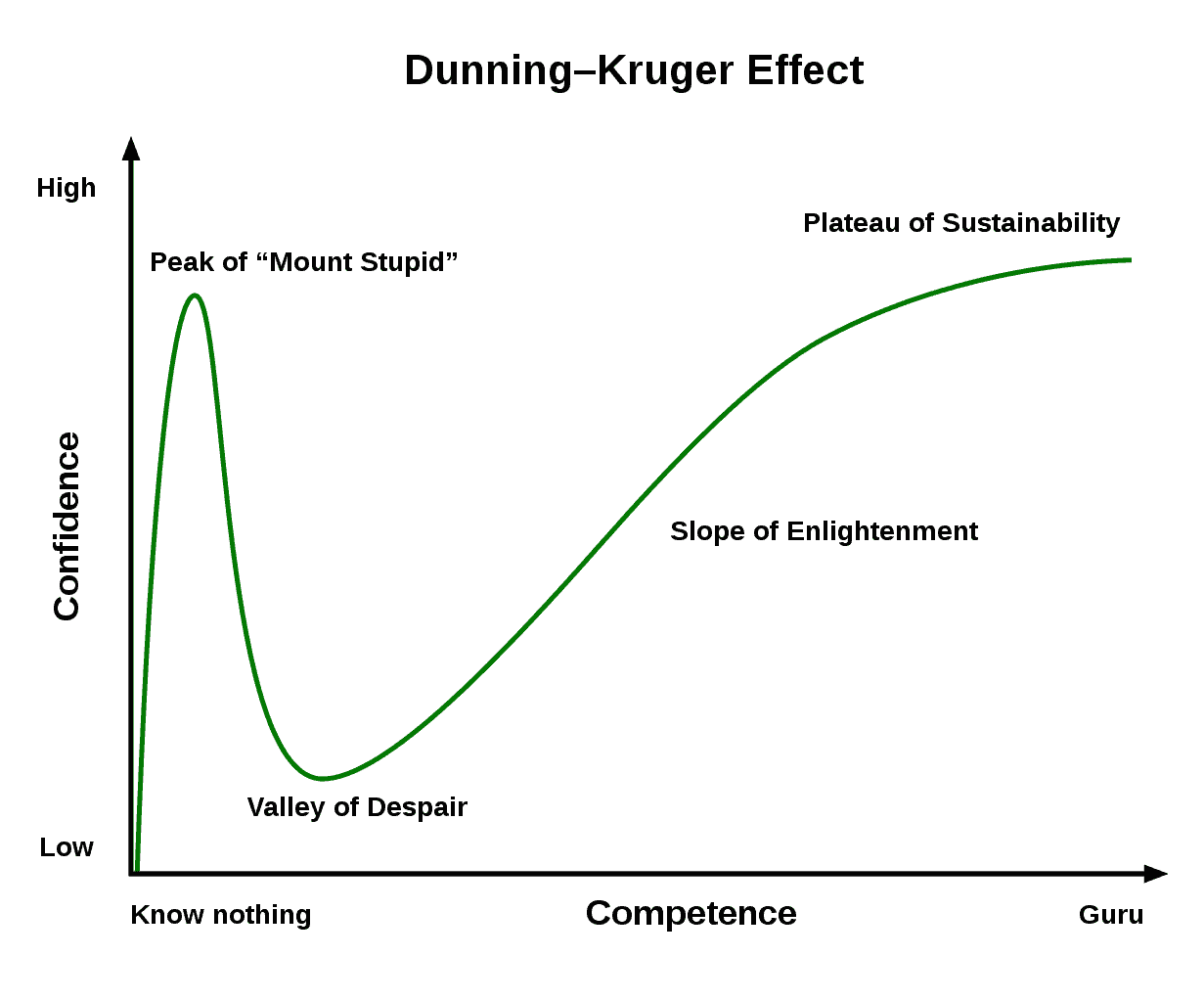

This report from BuiltIn found that 92 percent of teachers “understand the impact of technology in education.” I have no doubt that 92 percent of teachers possess a functional or even fluent literacy with educational technology, but that’s slightly different from grappling with, and reaching closure on, the larger ramifications and impact of technology on education at large. It was only 10 years ago that we didn’t have Google Classroom, Zoom, or EdPuzzle. For many of us, our classrooms weren’t even equipped with SmartBoards or document cameras back then. I’m dubious that in just over a decade, we have resolved the many tricky and tangled questions that technology has aroused. In some respects, our collective overconfidence seems to be a case of the Dunning-Kruger effect at work.

In 1995, McArthur Wheeler robbed two banks in broad daylight in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The 5’6” 270-pound bank robber would have been tough to miss under normal circumstances, but Wheeler had a surefire way to conceal his identity. You see, before going on his crime spree, Wheeler soaked his face in lemon juice. Wheeler knew that lemon juice could be used as an agent to render his face invisible to the bank cameras. As he was handcuffed by police just hours after robbing the second bank, he incredulously shouted, “But I wore the juice!”

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that results in people overestimating their competence or ability because they inflate the value or depth of their experience or knowledge in a certain domain. In education parlance, the Dunning-Kruger effect is best understood as the antithesis to the growth mindset.

So, how do we counteract the Dunning-Kruger effect? Well, it’s not complicated. Rather than be confident, we have to be curious. It’s an uncomfortable slide from the “Peak of ‘Mount Stupid’” to the “Valley of Despiar.” It’s a slide that requires us to be vulnerable and admit that we don’t have all the answers, but it is also this very slide that prompts us to challenge our preconceived beliefs and revisit our existing schematics with fresh eyes and an open mind. It is this slide that enables us to explore the educational trends that are shaping our future in an honest and scrupulous manner.

The rapid pace of technological advancement and its now inextricable presence in our classrooms should catalyze our curiosity to ask the tough questions about the future of teaching and learning. There are many questions for us to examine, but let’s start with a few that the exigencies of new and emerging technologies demand we interrogate.

1. What Constitutes Plagiarism?

Technology has made plagiarism easier to detect, but it has also made it easier to engage in. As technology evolves, plagiarism methods have taken new, complex, and sophisticated forms, which illustrates the need for educators to ask themselves what actually constitutes plagiarism in the modern classroom. Plagiarism is no longer limited to blatant acts such as peeking over a peer’s shoulder during a quiz or copying chunks of text from a Wikipedia entry; plagiarism now is more nuanced and raises questions of originality, authorship, and attribution. Consider Grammarly. Grammarly is a grammar and editing software that uses AI to analyze writing and looks for ways to improve it in real time by correcting verb tenses, suggesting synonyms, and offering clearer sentence structures. Just recently, a fellow middle schooler director here in Kentucky polled his students to learn how many of them use Grammarly. The results of this survey were shocking but unsurprising. 100% of his students have used Grammarly at least once in the last school year. Now, Grammarly cannot tell students what to write, autonomously generate sentences, or automatically make revisions to students’ work. In fact, I might posit that automated writing assistance gives students a chance to focus on the actual substance of an assignment. The issue is not that our students are using Grammarly, but that its use is ostensibly changing the nature of how students interact with writing assignments. And yet, in classrooms across the country, essay rubrics include the very criteria that Grammarly is tasked with fixing. As educators, we need to grapple with the consequences and opportunities that a software like Grammarly provides. If plagiarism policies are intended to ensure that teachers are provided with an honest glimpse into what students know, perhaps it's time for schools to consider whether to update our policies to better reflect the realities of learning in 2022.

2. Is There a Future for Essay Writing?

We know that automated writing assistants are changing the nature of essay writing, but are new technologies rendering essay writing obsolete altogether? It’s possible. Natural language processors are creating human-like content light-years ahead of every software to come before. Far more advanced than predictive text, which we’ve all likely encountered in Gmail and Google Docs, Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) is an autoregressive language model that uses natural language processing to generate long-form written responses that closely imitate the unique voice and stylistic flourishes of human authors. Increasingly GPT-3 is becoming scarily good at imitating human writing. It’s especially practiced and talented when following formulaic and predictable structure. Just take a look at the three-paragraph essay below. It was written by GPT-3 about GPT-3. All the user had to do was enter a few keywords and the algorithm took care of the rest.

In 2021, a team of researchers had a panel of professors create writing prompts in their respective subjects. The researchers then gave these writing prompts to a group of undergraduates, recent graduates, and GPT-3. The recent graduates and undergraduates had three days to respond to the prompt – it took GPT-3 only 20 minutes. The team of researchers anonymized the responses and had the panel of professors grade the anonymous submissions. Across five essays in five subjects, GPT-3 earned an average grade of a C. Cs aren’t exactly the gold standard in academia, but let’s not forget the old adage, “Cs get degrees.” For many decades, essays have been a staple of the schooling experience. Students write essays from lower school through graduate school. Essays are widely considered to be an efficient and effective means of isolating and assessing student knowledge. But, when a machine can write an essay as well as a human, what is the utility in teaching this skill? With the emergence, maturation, and accessibility of GPT-3, it’s incumbent on us, as educators, to consider how we are using essays to best capture our students’ imagination, develop their critical thinking skills, and accentuate those qualities that distinguish our students from software. If you want to explore the power and limitations of GPT-3 for yourself, take a look at Smodin.io, Jasper.ai, Copy.ai, Writelyai.com or join Google’s AI Test Kitchen.

3. Is There Such a Thing as Digital Natives?

Digital natives is a term that was popularized about two decades ago to describe a generation of students who never knew a time before the internet and the explosion of affordable digital technologies. By definition, all students in K-12 schools in 2022 would be considered digital natives. It is true that this generation of students is more connected than older generations. However, there are also many problems in this way of conceptualizing young people. The notion of digital natives assumes that students are natural users of digital technologies. But, we know that there isn’t such a thing – it’s not as though this younger generation has some fundamental and inborn biological or neurological predisposition to understand and use computers. This generation of students might have a greater predilection towards technology than older generations, but interest shouldn’t be conflated with expertise. We know from many studies the important role that educators play in helping students to turn their interests to expertise, but the powerful narrative around digital natives has had a disempowering effect on educators, who often feel that they have nothing to offer this generation of learners. The resulting hands-off approach is preventing students from developing both fundamental and complex digital skills. This is why typing classes have become largely extinct. Is typing any less vital a skill now than it was 20 years ago? Of course not. But, there is an assumption amongst educators that typing is a skill that students just innately possess. As a Middle School Director, I have seen firsthand the pitfalls of this thinking. A couple of months ago I was meeting with a 6th grader who had an outburst in their language arts class. During our conversation, this student expressed to me how much they dislike writing. As we dug deeper into this statement, it became evident that it wasn’t writing that this student didn’t enjoy, but typing. In fact, it sounded like this student really enjoyed writing, but that the act of typing was such a laborious process that this student grew frustrated and would begin to act out. I pulled up a typing game on my computer to see how dire the situation was. It turned out that this student was typing just 12 words per minute! It was then that I decided to implement basic typing standards across the middle school. If we want students to be successful as they move from middle school to high school, from high school to college, and from college to the professional world, students need a strong foundation in the digital basics. Students who type 12 words per minute are increasingly disadvantaged for the jobs of the emerging future. And those who are most and disproportionately disadvantaged by a lack of instruction in the basics are our historically marginalized students. These students tend to have less access to technologies, a lower quality of home Internet, and fewer people outside of school who can support them. This is why schools cannot fall victim to the digital native narrative. When we do so, we are exacerbating the inequalities of our society by turning our backs on our students who are most in need of our instruction and support.

Digital technologies are changing the educational landscape. As educators, we should not accept these changes in an uncritical fashion. TTWWADI is comforting and inertia is powerful, but we cannot shrug our collective shoulders and continue with policies, assignments, and narratives that are artifacts of a bygone era. As technology evolves, let us allow education to evolve alongside it by examining, debating, and embracing the changing nature of teaching and learning.